Faulkner, William. Absalom, Absalom! New York: Vintage International, 1986.

Review by: Michael Viox, Caitlin Parker, and Casandra Willett

An examination of race, culture, and the American literary imagination.

Life:

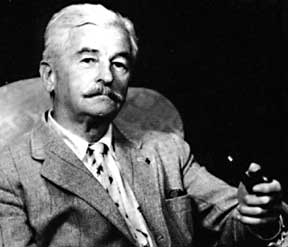

William Faulkner was born on September 25, 1897 in New Albany, Mississippi. His parents were Murry and Maud Butler Falkner. William later changed the spelling of his last name by adding the “u.” His family was a typical “Old Southern Family” (Nobel). His family moved to Oxford, Mississippi where he grew up. While in school, he met Phil Stone who was the first to recognize his literary talent and became Faulkner’s literary mentor (Padgett).

During the first world he joined the Canadian, and later the British, Royal Air Force. Although he had dropped out of high school, he enrolled in the University of Mississippi in Oxford. He dropped out of the University in 1920. His early jobs included working at a New York bookstore and working for a New Orleans newspaper called The Double Dealer. In 1925 Faulkner moved to New Orleans (Padgett).

Although he had just set down roots in New Orleans, Faulkner travelled to Europe. While in Paris, he wrote descriptions of the Luxembourg Gardens. These writing would later be revised for the closing of his novel Sanctuary (Padgett).

He married his childhood sweetheart, Estelle Oldham. The two were wed at College Hill Presbyterian Church, just north of Oxford. Estelle brought two children to the marriage from her previous relationship. They couple lived in Oxford. To make ends meet, he was now working nights at a power plant. Despite his financial burdens, he bought a house in Oxford and named it “Rowan Oak” (Padgett).

In 1931, Estelle gave birth to a daughter, Alabama. Alabama was born prematurely and only lived for a few days. In 1932, he took on a new job, mostly for finances, as screenwriter in Hollywood. In 1933, Estelle gave birth to the couple’s only surviving child. They named her Jill. Faulkner began working in Hollywood again where he met Meta Carpenter, the secretary and script girl for his coworker. Faulkner eventually began an affair with Carpenter (Padgett).

In the early 30’s, Faulkner took up flying. He bought a Waco cabin aircraft. Later he gave the Waco to his youngest brother, Dean, encouraging him to become a professional pilot. Dean crashed and died in the plane later in 1935. This left Faulkner filled with grief and guilt so he took care of Dean’s children (Britannica).

Although not technically an alcoholic, when Faulkner returned to Oxford in January 1936, he spent the first of many stays at Wright’s Sanitarium, a nursing home facility in Byhalia, Mississippi. Faulkner would go there to recover from his drinking binges (Padgett).

In 1936 he returned to Hollywood. Staying for under two years, he returned to Oxford. In January 1939, Faulkner was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Travelling to California in 1942, Faulkner, yet again, worked by writing screenplays. In March 1947, he publicly offended Hemingway at a debate and was forced to write an apology letter (Padgett).

Faulkner began another affair with a woman named Joan Williams in 1950. The two had begun a collaboration within their writing careers. Faulkner received many awards throughout his life. Two of these awards were the award of Legion of Honor and the Silver Medal of the Athens Academy (Padgett).

In March 1959, Faulkner broke his collarbone after he fell from a horse at Farmington. He was never the dame after his fall. On July 6, 1962, he fell from a horse again and was gravely injured. He signaled to be taken to the hospital and he died the same day of a heart attack at the age of 64. He was buried on July 7 at St. Peter’s Cemetery in Oxford (Padgett).

Writings:

While attending school at Ole Miss he published his first short story in the student paper and his first poem in The New Republic. He then published his first collection of poetry, The Marble Faun, with Stone’s financial support, in 1924. (Gibson)

Sometime during his travels, he gave up poetry to concentrate on fiction. A famous writer by the name of Sheerwood Anderson recommended him to the New York publishers Boni & Liveright, and in February 1926 they published his first novel, Soldiers’ Pay. It is novel stylistically ambitious and strongly evocative of the sense of alienation experienced by soldiers returning from World War I to a civilian world of which they seemed no longer a part. It is an unremarkable story and impressive achievement for William Faulkner. (Gibson)

In the next three years, he published two more novels—Mosquitoes, which is considered to be his weakest, and Sartoris, the first book set in what would later become his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi. Sartoris was originally titled Flags in the Dust but he had been having difficulty in finding a publisher so when the novel did appear, it was severely truncated. In 1973 Flags in the Dust was published. It is a long, leisurely novel, drawing extensively on local observation and his own family history that he had confidently counted upon to establish his reputation and career. (Britannica)

In 1929 he published his first major novel, The Sound and the Fury, which he says he had “written his guts” into. In this novel he combines a Yoknapatawpha setting with radical technical experimentation. The book experiments with unreliable narrators, multiple points of view, and successive "stream-of-consciousness" monologues. The three brothers of Candace (Caddy) Compson—Benjy the idiot, Quentin the disturbed Harvard undergraduate, and Jason the embittered local businessman—expose their differing obsessions with their sister and their loveless relationships with their parents. It is also narrated by the Compsons’ black servant, Dilsey, which provides the reader with new perspectives on some of the central characters. The novel contains a powerful yet essentially unresolved conclusion. Faulkner had always been willing to try new literary techniques, which tended to make his early writing inconsistent. But now his unerring ear and sense of place produced a book, according to one review, “worthy of the attention of a Euripides.” (Britannica and Gibson)

Between 1929 and 1932 Faulkner churned out more than 40 short stories. In 1930, he also published his next novel As I Lay Dying. It is centered upon the conflicts within the “poor white” Bundren family as it makes its slow and difficult way to Jefferson to bury its matriarch’s malodorously decaying corpse. Entirely narrated in 59 monologues by 15 characters that consist of the various Bundrens and people encountered on their journey, it is the most systematically multi-voiced of Faulkner’s novels. The novel ignores most of the conventions of traditional storytelling, such as chronological plotting and an authoritative point of view. It earned favorable reviews but mediocre sales. His next novel won him public acclaim. Published in 1931, Sanctuary is a novel about the brutal rape of a Southern college student. (Britannica and Gibson)

His next novel, Light in August, was a return to more traditional form. It revolves primarily upon the contrasted careers of Lena Grove, a pregnant young countrywoman serenely in pursuit of her biological destiny, and Joe Christmas, a dark-complexioned orphan uncertain as to his racial origins, whose life becomes a desperate and often violent search for a sense of personal identity, a secure location on one side or the other of the tragic dividing line of color. (Britannica)

In the next decade and a half he wrote four more novels, including Absalom, Absalom!, produced in 1936. In Absalom, Absalom!, Thomas Sutpen arrives in Jefferson from “nowhere,” ruthlessly carves a large plantation out of the Mississippi wilderness, fights valiantly in the Civil War in defense of his adopted society, but is ultimately destroyed by his inhumanity toward those whom he has used and cast aside in the obsessive pursuit of his grandiose dynastic “design.” By refusing to acknowledge his first, partly black, son, Charles Bon, Sutpen also loses his second son, Henry, who goes into hiding after killing Bon (whom he loves) in the name of their sister’s honor. Because this profoundly Southern story is constructed by a series of narrators with sharply divergent self-interested perspectives, Absalom, Absalom! is often seen, in its infinite open-endedness, as Faulkner’s supreme “modernist” fiction, focused above all on the processes of its own telling. (Britannica)

During this decade and a half he also wrote three short-story collections, most notably Go Down, Moses, yet another major work, in which an intense exploration of the linked themes of racial, sexual, and environmental exploitation is conducted largely in terms of the complex interactions between the “white” and “black” branches of the plantation-owning McCaslin family, especially as represented by Isaac McCaslin on the one hand and Lucas Beauchamp on the other. Six years separated Go Down, Moses from his next novel, Intruder in the Dust. (Britannica)

Intruder in the Dust published in1948, is a novel in which the character Lucas Beauchamp, reappearing from Go Down, Moses, is proved innocent of murder, and thus saved from lynching, only by the persistent efforts of a young white boy. Racial issues were again confronted, but in the somewhat ambiguous terms that were to mark Faulkner’s later public statements on race: while deeply sympathetic to the oppression suffered by blacks in the Southern states, he nevertheless felt that such wrongs should be righted by the South itself, free of Northern intervention. (Britannica)

Screenplays and Film:

The first film the William Faulkner was a part of was the film Flesh. Faulkner was and uncredited writer in Flesh which was released in 1932.

In the 1930’s Howard Hawks invited William Faulkner to Hollywood to be a screenwriter for the film that he was directing. As his work was slow and there was an increasing demand to provide for his growing family William Faulkner accepted the offer. William was officially credited for writing six Hollywood screenplays, five of which were directed by Howard Hawks.

A few of the screenplays that Faulkner wrote were Today We Live (1933), The Road to Glory (1936), Slave Ship (1937), Submarine Patrol (1938), Air Force (1943), To Have and Have Not (1944) and, The Big Sleep (1946). The most notable of these would be To Have and Have Not as is was the screen adaption of the Novel written by Ernest Hemingway.

A legendary, but possibly apocryphal, story about Faulkner relates how, after he had been hired by 20th Century-Fox as a screenwriter, Faulkner had been sitting around the Fox writers building for a few weeks without having done anything. A producer asked what he was doing, and Faulkner replied “nothing”. The producer asked if he had any ideas for a story. Faulkner replied that he had, but he was having difficulty writing in the studio and would be better suited to write at home. The producer told him it was OK to go home, assuming that Faulkner was referring to the home in Hollywood that the studio was renting for him. A few days later the producer called the hotel in which, was the room that the studio was renting for Faulkner. The producer learned that Faulkner had indeed gone home--to Oxford, Mississippi.

In 1942 The Saturday Evening Post published a short story written by William Faulkner titled Two Soldiers. The story was later adapted into a film directed by Aaron Schneider and won an Oscar in 2004 for best short film.

Works Cited:

Gibson, Christine. "William Faulkner's Struggle for Greatness." American Heritage.com. 25 Sept. 2007. 14 Jan. 2009 http://www.americanheritage.com/people/articles/-web/20070925-william-faulkner-southern-gothic-yoknapatawpha-mississippi>.

Padgett, John B.. "William Faulkner." Mississippi Writers Page. 2008. The University of

Mississippi English Department. 14 Jan 2009

"William Faulkner." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 15 Jan. 2009 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/202695/William- Faulkner>.

"William Faulkner". Internet Movie Database. 13 Jan. 2009

"William Faulkner The Nobel Prize in Literature 1949 ." Nobelprize.org. 2009. The Nobel

Foundation 1949 . 14 Jan 2009